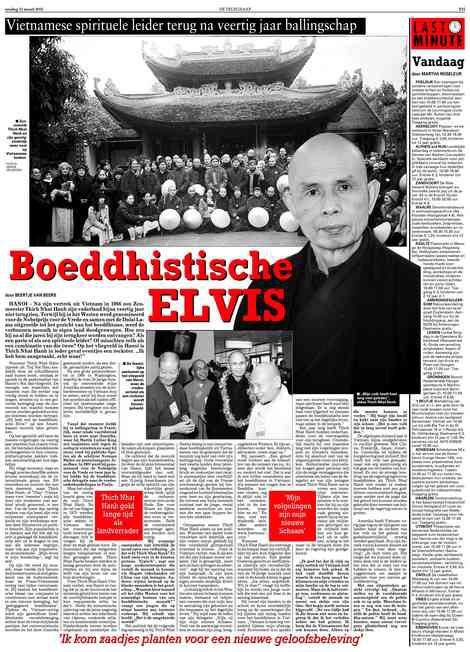

Like a Buddhist Elvis

HANOI, 2006- After leaving Vietnam in 1966 it would take Thich Nhat Hanh almost 40 years to return to his homeland. How would he be welcomed back? Would he be regarded as an outcast, a spiritual leader or maybe even a combination of the two? Whatever the case, when we arrive at Hanoi airport, Thich Nhat Hanh is a rock star. “I touched him, with my own hands!”

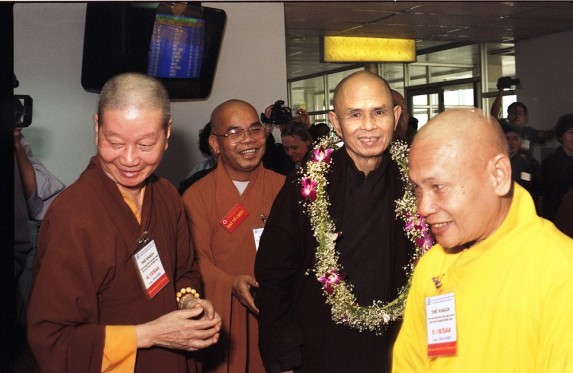

When the sliding doors open and Thich Nhat Hanh (pronounced Titch-Naught-Han) finally enters, panic breaks out at the arrival hall of Hanoi’s Noi Bai airport. Moments before the crowd of about a 1000 people were peacefully praying and chanting, but now they rush towards the Zen monk. People are being pushed aside, flowers trampled upon. Later an American monk would jokingly comment that upon arrival “[Thich Nhat Hanh] looked like a Buddhist Elvis!” At the moment supreme the followers burst into tears, it has been a long 40-year wait. On the periphery the police officers in their Communist green outfits watch the chaos and nervously smoke their cigarettes.

He flies economy and wears the same humble brown monk’s coat as the international group of 200 monks and nuns that travel with him. Yet Thich Nhat Hanh, or ‘Thay’ (Vietnamese for `teacher’) as his students respectfully call him, is a star. He has written over 80 books, millions of which have been sold worldwide. His workshops are attended by both movie stars and politicians. His popularity is a direct result of his inspiring life story and his ability to communicate Buddhist teachings in a clear manner. “My life is my message,” he says. He became a monk at the age of 16 but confined by the convent walls he quickly began to feel isolated from the outside world where the French-Vietnamese War was causing much suffering. He started a movement that became known as `engaged Buddhism’ which combined Buddhist teachings with active social work. However, during the Vietnam War both the Communist North and the Non-Communist, US-supported South considered the Buddhist resistance movement a third, dangerous party in the conflict.

After a big press conference in Washington DC in 1966, during which the then 39-year-old monk begged America to stop bombing Vietnam, he was officially labeled a traitor by both the North and South. His life was in serious danger if he were to return to Vietnam. From that moment on he lived in exile in France, continuously traveling back and forth between France and America, where he inspired Martin Luther King to speak out against the war and gained prominent supporters including writer Norman Mailer and protest singer Joan Baez. In 1967 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and two years later he led the Buddhist delegation at the Paris peace talks. But for Thich Nhat Hanh the end of the war did not mean peace. After the fall of Saigon in 1975 the Communist regime forced all Buddhist sects in Vietnam to join one state-controlled church. Monks that refused were either placed under temple arrest or imprisoned and Thich Nhat Hanh’s books were confiscated by the authorities. The monk would spend half his life a million miles away from home.

When Thich Nhat Hanh left Vietnam Hanoi was a quiet place where you could hear the rushing sound of girls riding by on their bikes, wearing their white ‘ao dais’. Ever since the economic boom of the 1990s a cacophony of car horns, smoke-belching exhaust pipes and noisy motor scooters dominates the city. Mopeds rush by carrying anything from chickens and sheets of glass to entire families. The morning that the monk starts his meditative walk through Hanoi’s busy city center, the noise seems more overwhelming than ever. But while he’s leading the silent procession, all the while holding hands with a 12-year-old American boy, the noise seems to lessen and the busy traffic parts like the Red Sea before Moses. Even the ever-present police officers keep a low profile. Bystanders literally drop their jaw in amazement. “Is that the real Thich Nhat Hanh? There was nothing about this in the newspapers. Typical,” says a young fashion designer, who learned about the monk through illegal copies of his lectures from China. Others point and laugh at the Caucasian monks. “Why would someone from the rich West choose to live as a Buddhist monk,” asks a boy who sells cards on the streets to tourists. He shakes his head: “It’s the world turned upside down.”

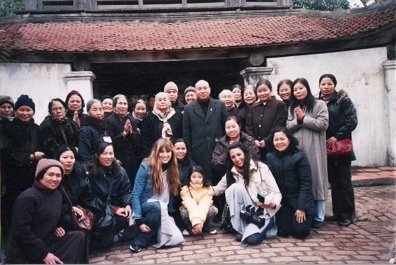

The audience that attends Thich Nhat Hanh’s lecture in a temple the following day largely consists of Vietnamese of the generation that still know the monk from before his exile. Old women with black teeth – the result of years of chewing beetle nut – and men wearing black berets – a remnant of the French occupation – sing and cry while throwing flowers at the Zen master and his following as they enter the room. They stand in stark, almost comical contrast to the young, mostly Western monks and nuns who tower over them. Thich Nhat Hanh takes his seat on the stage. When a number of women literally throw themselves at his feet he smiles friendly while urging them to get up. “When I left Vietnam I was like a cell that was forced to leave its body. This is dangerous because a cell can dry up and die,” he says in his opening statement. You can hear the relief in his voice about finally being able to directly talk to his people. “Thankfully I was able to create a new body in the West, made up of millions of people who learned about my teachings and applied them in everyday life.” He points at his delegation. “Look, they are my new body.” Many of the monks and nuns present here are young, well-educated Westerners. Among them are architects, doctors and lawyers. He pauses. “A belief system has to meet the needs of today’s people. Only then will it be practiced instead of drying up. That is what I would like to change about Buddhism in Vietnam. When people ask me how they can find Buddha I always tell them: not in the past, not in the future but in the here and now. In other words at www.hereandnow.com,” he adds with a beaming smile.

When Thich Nhat Hanh welcomes us at the temple where he is staying he looks a lot more fragile than he did on stage. He has a smooth Eastern face and ageless appearance but when he coughs you can tell that the journey has taken a bit of a toll on the 78-year-old monk. “Please sit down. Would you like some tea,” he courteously asks, while nodding to a young monk who stands waiting with a pot of tea. He folds his hands in his lap and immediately brings up the comments he made during his lecture about Buddhism in Vietnam. “In my absence Vietnam has changed profoundly. There has been enormous economic growth but spiritually things have stagnated here. There is still a lot of superstition and people apply Buddhist teachings in temple rather than in daily life.”

It took Thich Nhat Hanh more than a year of negotiations before he was able to return. He and his followers were eventually allowed to come back for four months of touring temples and convents on the condition that he would, under no circumstance, deviate from the set route. Beforehand, Thich Nhat Hanh had to hand in transcripts of his lectures, and foreign journalists weren’t given a press visa. (Photographer Venus Veldhoen and I travel as part of the delegation, dressed in nun’s robes) You can tell that during his public performances the monk is carefully picking his words although he often hints at the paradox that millions of believers now have the freedom to practice their religion just as long as they do so at government-approved temples.

“I came back to plant seeds for a new religious experience,” says the monk as he takes a sip of his tea. The cup is immediately refilled. “I have to admit that after I left Vietnam I was terribly homesick. I kept having the same dream in which I had to climb a mountain in order to meet my friends and family on top. But halfway up the mountain he would see them suddenly disappear.” He pauses. “After a while I stopped having that dream and I realized that I had left the past behind me. I hope that the Vietnamese people can do the same. It is the only way to move on.” He bows his head and looks at his hands that rest in his lap. “These people have suffered so much for so long.”

During the last 100 years Vietnam has been involved in almost continuous conflict with China, France, Japan, America, Cambodia and with itself during the civil war. It has made the Vietnamese tough but also suspicious of foreign influences. In that light the authorities’ strict attitude towards Buddhists like Thich Nhat Hanh could have less to do with a godless Communist dogma and more with the fear that religion could be used by outside influences to topple the government. Just last year America put Vietnam on a list of countries where people’s rights in terms of freedom of religion were being trampled on. Could his visit be used as propaganda for this government? “It’s possible. The only thing we can do during this visit is show the leaders that they don’t need to fear us.” He continues: “That is why we appreciate the continuous presence of the police. And this way they also learn a thing or two. Yes, even the police have Buddha nature,” he laughs. He coughs once more and, with a smile on his face, takes another sip of tea.

Originally published in Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf, in 2006. Pictures by Venus Veldhoen.